Recreating PlanetScale’s pg_strict in Rust

Recently PlanetScale released a pg_strict extension here and I wanted to see if I could replicate it and release it open source, since I had some experience writing Postgres extensions in Rust like uids-postgres and slugify-postgres.

So, I wrote a small Postgres extension in Rust of the same name: pg_strict. The goal is the same as PlanetScale’s extension: block UPDATE and DELETE statements without a WHERE clause.

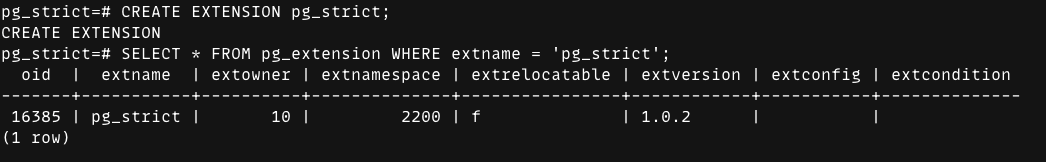

Installing it is a normal CREATE EXTENSION pg_strict; flow. The rest of this post is about how to reliably block unsafe statements at the right stage of Postgres’ pipeline.

I thought the build would be straightforward. It was not. The hard part wasn’t the Rust code; it was choosing the right phase of the Postgres pipeline and the right parser.

This post is a detailed log of the evolution of this extension: from a naive string-parsing proof of concept to integrating deeply with Postgres’ own analysis phase.

The problem

We all know this problem, right?

UPDATE users SET status = 'inactive';

DELETE FROM sessions;This is valid SQL and a data incident waiting to happen. The extension should:

- blocks loudly when it matters

- stays simple enough to keep enabled

- feels native to Postgres (GUCs, roles, sessions)

Primer: Postgres query pipeline and hooks

Before the build log, here is the mental model that made the rest of the decisions obvious. Postgres processes queries in distinct stages, and pgrx allows us to hook into them.

What each stage actually gives you:

Parser: syntax tree only, no semantic guarantees.

Parse/Analyze: a real

Querytree withcommandType,jointree, andquals. This represents the intent of the query.Tiny explanation:

commandType: UPDATE, DELETE, etc.jointree: the FROM/JOIN tree (what relations are being scanned/joined).quals: the boolean filter expression tree (typically theWHEREconditions). If it’s null, there’s no filter.

Planner: a plan tree optimized for execution.

Executor: row processing and side effects. This is where the query actually runs.

My journey involved moving from the bottom (Executor) to the top (Analyzer).

Hook Phase Explorer

Five approaches, one correct answer. Click each stage to see where it hooks into the Postgres pipeline and why it works or fails.

Fires right after Postgres builds the full semantic Query tree — before the planner runs. Zero parsing overhead: just reads jointree→quals, a pointer that's already in memory. Fully correct and efficient.

Stage 0: Proof of Concept (Executor Hook)

To start, I just wanted to verify I could intercept a query at all. I set up a basic ExecutorRun_hook. This runs right before Postgres starts executing the plan.

The goal here was simple: Can I see the SQL string and stop execution?

This worked. I verified that pgrx hooks were wired correctly. Now I needed to actually parse that SQL string to see if it had a WHERE clause.

Stage 1: The Tree-sitter Attempt (Failed)

My first instinct for parsing was Tree-sitter. It’s modern, fast, and I’ve used it before. I tried to pull in tree-sitter-sql (or Postgres specific grammars) inside the hook to analyze the string.

I spent a few hours fighting build scripts and linking issues. It felt like overkill to embed a generic parser when I was already running inside a database engine that has a world-class parser built-in. I abandoned this path quickly.

Stage 2: The sqlparser Approach (Flawed)

Next, I turned to the native Rust crate sqlparser. This is a popular SQL parser written in pure Rust.

I kept the ExecutorRun_hook. Inside the hook, I took QueryDesc.sourceText (the raw SQL string) and fed it into sqlparser.

impl QueryAnalyzer {

/// Return all UPDATE/DELETE operations that are missing a WHERE clause.

pub fn missing_where_operations(&self) -> Vec<Operation> {

let mut missing = Vec::new();

for stmt in &self.statements {

match stmt {

// Check UPDATE

Statement::Update { selection, .. } if selection.is_none() => {

missing.push(Operation::Update);

}

// Check DELETE

Statement::Delete { selection, .. } if selection.is_none() => {

missing.push(Operation::Delete);

}

_ => {}

}

}

missing

}

}Why this failed

The Rust code was clean, but sqlparser is not Postgres.

- Dialect Drift:

sqlparseris an approximation. Valid Postgres queries (like complexUPDATE ... FROMor specific casting syntax) often failed to parse in Rust, causing the extension to error out on perfectly valid SQL. - Double Parsing: I was forcing the CPU to parse every query string twice—once by Postgres to run it, and once by me to check it.

I realized that as long as I was using an external parser, I would never be 100% compatible.

Stage 3: Using Postgres’ Own Parser (Correct logic, wrong phase)

To solve the dialect drift, I replaced sqlparser with pg_parse_query—the exact C function Postgres uses internally.

I was still in the Executor phase. I wrapped the unsafe C function using PgTryBuilder to handle panics safely across the FFI boundary.

impl QueryAnalyzer {

pub fn new(query_string: &str) -> Result<Self, Box<PgSqlErrorCode>> {

let c_query = CString::new(query_string)

.map_err(|_| Box::new(PgSqlErrorCode::ERRCODE_WARNING))?;

// Wrap the C call in a try-block to catch Postgres errors

PgTryBuilder::new(|| {

memcx::current_context(|_mcx| unsafe {

// The Source of Truth: Postgres' own parser

let raw_list = pg_sys::pg_parse_query(c_query.as_ptr());

collect_parsed_statements(raw_list)

})

})

.execute()?

}

}This solved correctness. Edge cases like DELETE ... USING or complex CTEs were now handled perfectly because we were using the source of truth.

But it was inefficient.

I was taking the SQL string and asking Postgres to parse it… right after Postgres had finished parsing it.

Stage 4: Parse-time enforcement (The “Correct” Way)

I realized I needed to move “left” in the pipeline. I shouldn’t be re-parsing the string; I should be looking at the work Postgres already did.

I switched from ExecutorRun_hook to post_parse_analyze_hook. This hook fires after Postgres has parsed the SQL and verified the semantics (like table existence), but before the planner runs.

Crucially, this gives us access to the Query struct—the semantic tree of the query.

The Hook

The hook signature is cleaner. We don’t need to extract strings or manage memory contexts for parsing. We just look at the pointer:

#[pg_guard]

unsafe extern "C-unwind" fn pg_strict_post_parse_analyze_hook(

pstate: *mut pg_sys::ParseState,

query: *mut pg_sys::Query,

jstate: *mut pg_sys::JumbleState,

) {

// 1. Run the previous hook (standard chaining pattern)

if let Some(prev_hook) = unsafe { PREV_POST_PARSE_ANALYZE_HOOK } {

unsafe { prev_hook(pstate, query, jstate) };

}

// 2. Run our check on the prepared Query tree

unsafe { check_query_strictness_from_query(query) };

}We no longer guess if a WHERE clause exists by looking for the word “WHERE” or checking RawStmt nodes. Postgres has already normalized this into the jointree.

If jointree->quals is not null, there is a filter. It’s that simple.

unsafe fn analyzed_query_operation(query: *mut pg_sys::Query) -> Option<(Operation, bool)> {

if query.is_null() {

return None;

}

// 1. Check the command type (UPDATE, DELETE, etc.)

let command_type = unsafe { (*query).commandType };

let operation = match command_type {

pg_sys::CmdType::CMD_UPDATE => Operation::Update,

pg_sys::CmdType::CMD_DELETE => Operation::Delete,

_ => return None,

};

// 2. Check the Join Tree for qualifications (WHERE clause)

let jointree = unsafe { (*query).jointree };

let has_where = if jointree.is_null() {

false

} else {

// "quals" contains the expression tree for the WHERE clause

unsafe { !(*jointree).quals.is_null() }

};

Some((operation, has_where))

}This approach has zero parsing overhead. It just reads a few pointers from memory structures that already exist.

Demo: CTEs and what counts as a “WHERE”

Because the check is based on the analyzed Query tree, it’s specifically looking for a top-level qualification (jointree->quals) on the actual UPDATE/DELETE.

That means a WHERE clause inside a CTE does not count. A WHERE ... IN (SELECT ...) on the update does count.

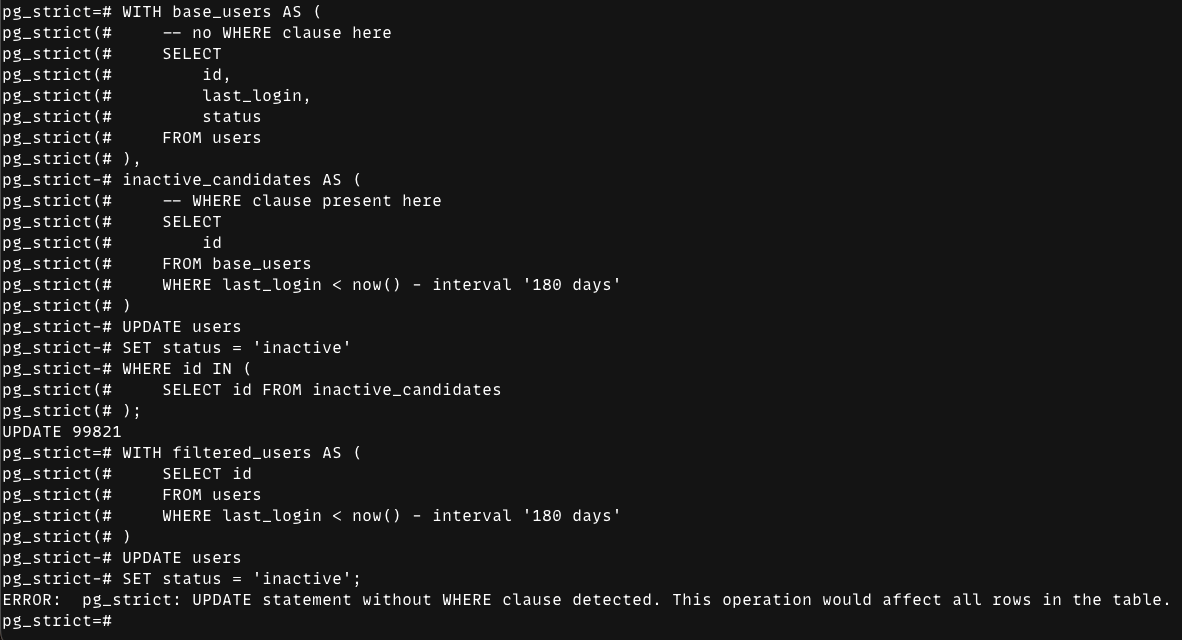

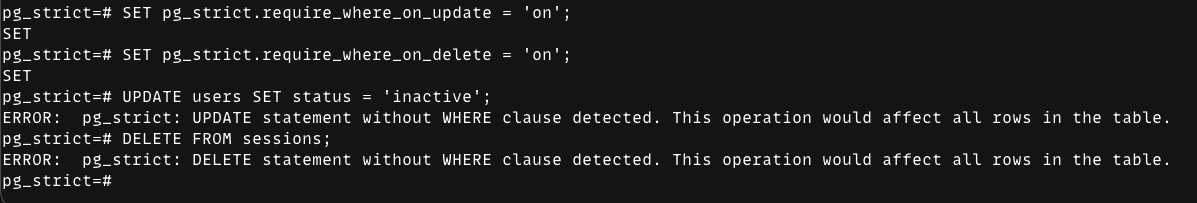

Stage 5: Configuration via GUCs

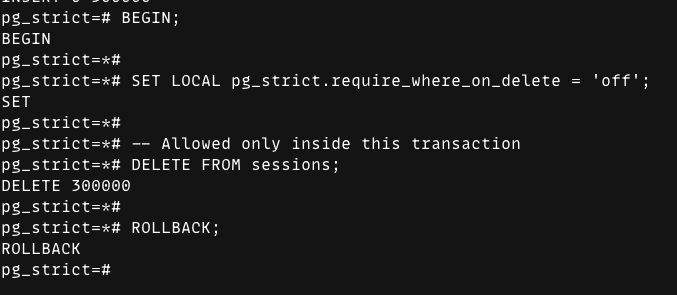

With the core logic solid, I needed to make the extension configurable to match PlanetScale’s behavior. Users need to be able to toggle this on/off per role or per transaction.

I used GUC (Grand Unified Configuration) — Postgres’ native configuration system.

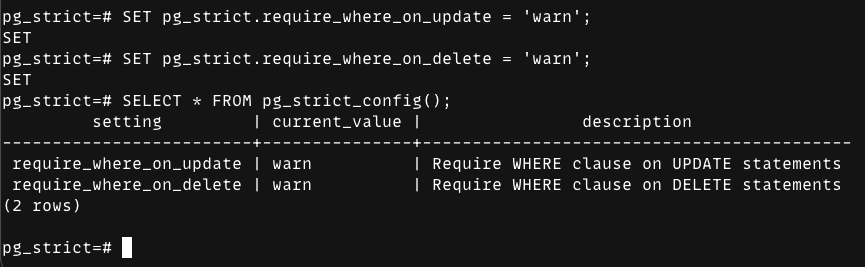

What it looks like in practice (psql)

Start by checking the extension’s current settings:

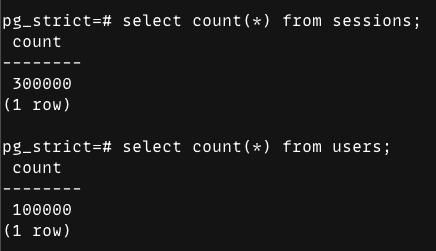

Here’s the table state I used for the examples below (so the row counts in the output make sense):

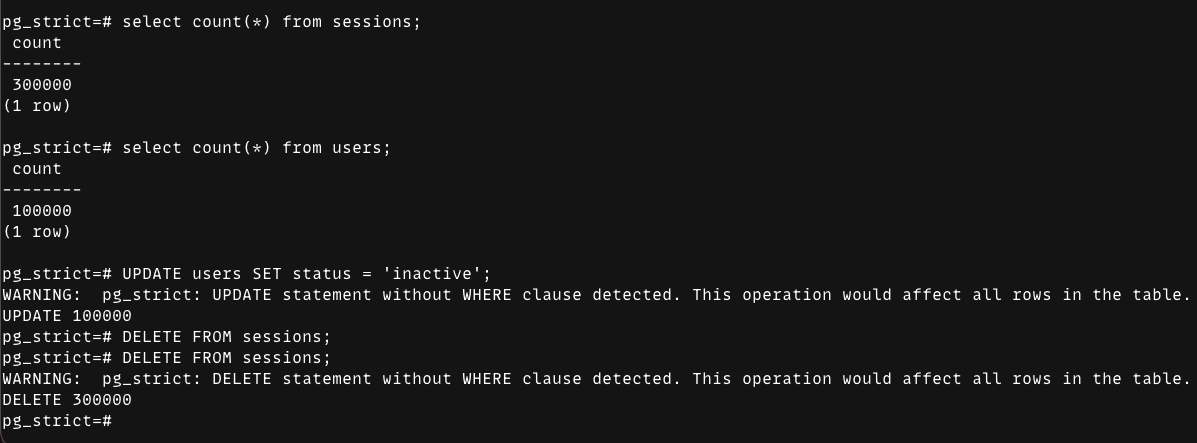

Warn mode

In warn, the extension logs a warning but allows the statement to execute:

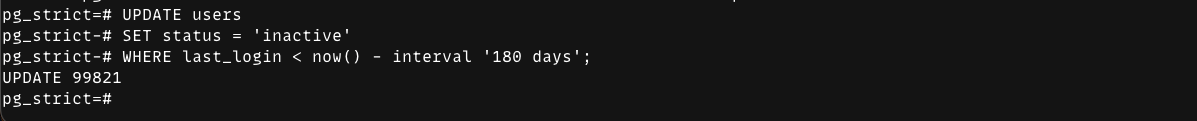

On mode

In on, the extension blocks unsafe statements with an error:

And when you do include a WHERE, the query runs normally:

Implementing GUCs with pgrx

#[derive(Clone, Copy, Debug, PartialEq, Eq, pgrx::PostgresGucEnum)]

pub enum StrictMode {

Off,

Warn,

On,

}

static mut REQUIRE_WHERE_ON_UPDATE_MODE: Option<GucSetting<StrictMode>> = None;

static mut REQUIRE_WHERE_ON_DELETE_MODE: Option<GucSetting<StrictMode>> = None;

pub fn init_gucs() {

unsafe {

// Define the GUCs so they appear in postgresql.conf / SET commands

GucRegistry::define_enum_guc(

cstr(b"pg_strict.require_where_on_update\0"),

/* ... description ... */

&mut REQUIRE_WHERE_ON_UPDATE_MODE,

GucContext::Userset,

GucFlags::default(),

);

// ... same for delete ...

}

}Now the extension flows like this:

pg_strict Playground

Configure the extension and try your own SQL. The check mirrors what post_parse_analyze_hook reads from the query tree — including CTE edge cases.

require_where_on_updaterequire_where_on_deleteWHERE inside a CTE does not satisfy the top-level jointree→quals check — only a WHERE on the UPDATE/DELETE itself counts.

This allows for powerful workflows:

ALTER ROLE app_user SET pg_strict.require_where_on_delete = 'on'(Safety for apps)SET LOCAL pg_strict.require_where_on_delete = 'off'(Override for specific migrations)

Here’s the “override for one transaction” pattern in action:

Final Architecture

The architecture is deliberately simple:

- lib.rs: Entry point.

- guc.rs: Manages configuration.

- hooks.rs: The

post_parse_analyze_hookthat reads theQuerytree. - analyzer.rs: Contains the safe wrappers around Postgres internals (used mostly for unit testing the logic without running a full DB).

Installing pg_strict

If you want to try the extension yourself, here are the quickest install paths.

Option 1: Pre-built binaries (recommended)

Pre-built binaries are available for Linux (x86_64) on the GitHub Releases page for pg_strict. Download the archive for your PostgreSQL major version, extract it, then copy the extension files into Postgres’ extension directories:

# PostgreSQL 15 (example)

wget https://github.com/spa5k/pg_strict/releases/download/v1.0.1/pg_strict-1.0.0-pg15-linux-x86_64.tar.gz

tar -xzf pg_strict-1.0.0-pg15-linux-x86_64.tar.gz

sudo cp pg_strict.so "$(pg_config --libdir)/"

sudo cp pg_strict.control "$(pg_config --sharedir)/extension/"

sudo cp pg_strict--*.sql "$(pg_config --sharedir)/extension/"Then enable it in the database:

CREATE EXTENSION pg_strict;Option 2: Build from source

Prerequisites:

- Rust nightly toolchain

cargo-pgrx(README uses0.16.1)- Standard PostgreSQL build deps (including

libclang)

Build:

cargo install cargo-pgrx --version 0.16.1 --locked

cargo pgrx init

# pick one: pg13 / pg14 / pg15 / pg16 / pg17 / pg18

cargo build --no-default-features --features pg15On macOS you may need:

export BINDGEN_EXTRA_CLANG_ARGS="-isystem $(xcrun --sdk macosx --show-sdk-path)/usr/include"Install the built extension:

PG_LIB="$(pg_config --libdir)"

PG_SHARE="$(pg_config --sharedir)"

# Linux

sudo cp target/debug/libpg_strict.so "$PG_LIB/"

# macOS

sudo cp target/debug/libpg_strict.dylib "$PG_LIB/"

sudo cp pg_strict.control "$PG_SHARE/extension/"

sudo cp pg_strict--*.sql "$PG_SHARE/extension/"Enable:

CREATE EXTENSION pg_strict;Verify

SELECT * FROM pg_extension WHERE extname = 'pg_strict';

SELECT pg_strict_version();

SELECT * FROM pg_strict_config();What I would do differently next time

- Trust the internal parser immediately: Any other parser is a compatibility tax.

- Pick the hook by data shape: If you need to understand the query’s intent, choose

parse/analyze. If you only need execution stats, go forExecutor. - Fail closed: If you cannot parse or analyze, block the query.

If you are building your own extension

This is the distilled checklist I now follow:

- Decide on the hook based on the data you need, not convenience.

- Use Postgres’ own parser instead of re-parsing SQL text.

- Keep unsafe code tiny and local.

- Use GUCs so your extension feels native.

- Build tests around real-world SQL (CTEs, Joins, RETURNING), not just toy examples.

- PGRX has a lot of great documentation and examples to help you get started, with all the hooks and functions you need to build your extension.

That’s the full story. pg_strict is small on purpose, but the path to get there taught me how Postgres actually works under the hood. If you’re writing your own extension, start where I ended up.

GitHub

Try pg_strict on GitHub

- Repository: github.com/spa5k/pg_strict

- Releases (prebuilt binaries): github.com/spa5k/pg_strict/releases

If this extension helps your team avoid accidental full-table updates or deletes, a GitHub star helps a lot.

Citation

PlanetScale’s pg_strict documentation